KBS - Know Bit of Somethings

"Camus in the Alps: Reflections on Evil, Resistance, and the Nature of Humanity"

While the residents of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a remote village in the Alps, were busy doing what they believed was "the right thing to do," another visitor had his own vision of what that meant.

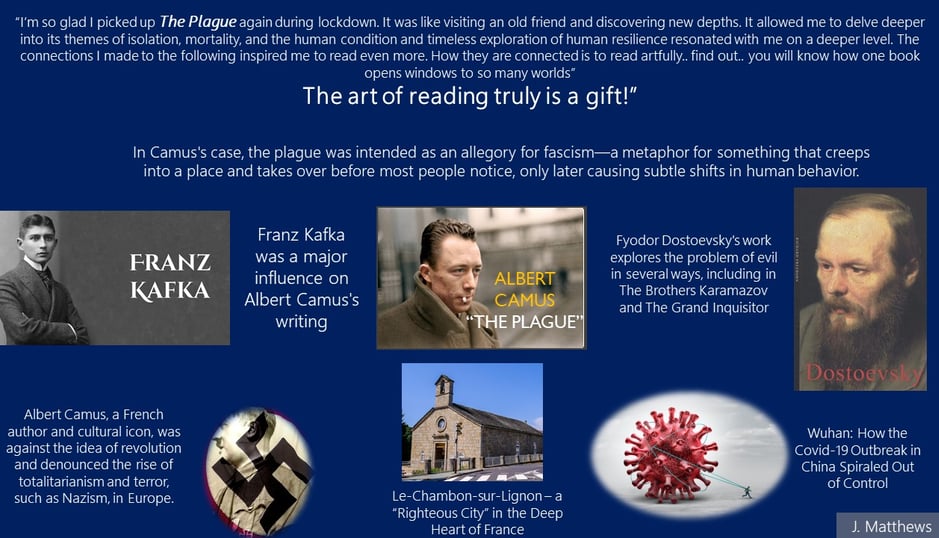

Albert Camus’s time in the French Alps, particularly in the small village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, significantly influenced his understanding of resistance and moral courage. In January 1942, he relocated to this region for medical treatment, seeking respite from tuberculosis. What began as a quest for health quickly transformed into a period of intense observation and reflection on human behaviour in the face of adversity. This alpine village, steeped in its own history of defiance and solidarity, provided Camus with a unique lens through which he could explore the complexities of human morality and the existential dilemmas posed by war and suffering.

During this period, Camus witnessed a remarkable act of civil resistance on August 10, 1942, when a group of young villagers confronted Cabinet Secretary Lamirand at the local Protestant church. They openly protested against the July 17 roundup of Jews, marking one of the first organized acts of defiance against the Vichy regime in that region. This event was not merely a local protest but part of a broader resistance movement emerging throughout France, as ordinary citizens began to challenge the injustices perpetrated by the state. The courage exhibited by these villagers in the face of authority profoundly impacted Camus, solidifying his belief in the necessity of moral action against oppression.

Isolated in the serene yet tumultuous backdrop of the Alps, Camus turned his attention to writing. It was here that he began crafting his second major cycle of works, which would become central to his philosophical inquiries into revolt and the human condition. His experiences and observations in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon directly informed the themes he explored in his subsequent novels, notably The Plague and The Misunderstanding. The bravery of the villagers, coupled with their historical struggles as Calvinist Protestants facing persecution, became a source of inspiration for Camus’s exploration of resistance against evil. In The Plague, he delves into the responses of ordinary people when confronted with overwhelming injustice and the pervasive nature of evil that threatens to engulf them.

Following the Allied invasion of North Africa on November 11, 1942, the German forces moved to occupy Vichy France, effectively trapping Camus in the Alps until late 1943. In his journals, he vividly described this period as feeling "besieged like rats." This imagery of entrapment and isolation would become central to the themes explored in The Plague, reflecting the psychological and emotional turmoil experienced by those living under oppressive regimes. Camus’s own sense of isolation mirrored the broader human condition, emphasizing the existential struggle individuals face when confronted with the absurdity of their circumstances.

Interactions with the local population further deepened Camus’s understanding of resistance and moral courage. He observed the significant risks that villagers undertook to shelter approximately 5,000 Jewish refugees fleeing persecution. The history of these villagers, who had resisted religious persecution from their Catholic neighbours, provided a poignant backdrop for Camus’s exploration of solidarity and resilience. Their acts of bravery were not just isolated incidents but part of a larger tapestry of human resistance against tyranny and oppression. Camus’s experiences in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon solidified his conviction that even in the face of absurdity, humanity has the capacity to rise above indifference and engage in moral action.

While the devastation of World War I had been viewed by many as humanity’s worst catastrophe, the onset of World War II proved even more cataclysmic. Intellectuals and thinkers of the time anticipated that this new wave of destruction would force society to undergo deep and lasting changes. However, the swift reversion to a semblance of normalcy following the war puzzled even the most astute minds. Among those grappling with this phenomenon was Albert Camus, whose works The Plague and The Fall reflect on this troubling tendency of society to quickly forget its collective trauma and resume its routine existence.

Camus wrestled with the nature of evil, exploring it through the lens of his philosophy of the absurd. Rather than seeking to understand the reasons behind suffering, injustice, and random violence, he focused on how humanity should respond to a world riddled with inexplicable and senseless evil. In The Plague, the spread of a deadly epidemic serves as a powerful symbol for the moral decay of society and the pervasive nature of evil. The narrative follows the residents of the afflicted city as they confront the trials and upheaval brought by the plague. Yet, the disease is more than just a physical threat; it acts as an allegory for the insidious rise of Nazism and the broader human experience of evil.

The characters in The Plague serve as representations of various philosophical perspectives on suffering and moral responsibility. Through figures such as Dr. Rieux, who embodies the spirit of scientific inquiry and humanism, and Father Paneloux, whose theological interpretations of suffering reflect a religious perspective, Camus examines the diverse belief systems people use to confront the looming shadow of absolute evil. This interplay between different worldviews allows for a rich exploration of the human condition, particularly regarding how individuals interpret and respond to suffering.

A compelling theme within The Plague is humanity’s tendency to evade or dismiss the reality of evil. Initially, many townspeople underestimate the seriousness of the plague, viewing it as just another illness rather than a significant threat. As the death toll rises, they seek cosmic or spiritual explanations, desperately trying to rationalize the outbreak. However, Camus reveals that these attempts to find meaning in suffering may serve as a way to avoid confronting the stark reality of evil itself. The novel suggests that the only truly meaningful response to such a threat is not in analyzing its causes but in facing it directly and actively fighting against it.

Camus delves deeply into the theme of evil and the human response to it, particularly through the existential dichotomy of solitude and solidarity. This tension is central to the experiences of the residents of Oran, where quarantine separates individuals from their loved ones while simultaneously binding them together in a shared struggle against the plague. This microcosm reflects the broader societal experience, posing a critical question: do individuals retreat into solitude, or do they work collectively for the common good?

Father Paneloux’s perspective on the plague, viewing it as divine punishment intended to provoke reflection and repentance, underscores a religious interpretation of suffering. In his first sermon, he suggests that the plague is God’s punishment for humanity's sins, arguing that suffering—especially that of innocents, such as children—must be accepted as part of God's inscrutable will. This theological stance highlights a form of solidarity born from faith, urging believers to accept suffering as a test of their convictions. However, Paneloux’s reasoning falters under the weight of human anguish, forcing the faithful to grapple with the complexities of “hard love” and total surrender.

In contrast, characters such as Dr. Rieux, Rambert, Tarrou, and Castel approach the plague as an arbitrary and inexplicable occurrence, emblematic of the Absurd. Unlike Paneloux, they do not view the plague as a divine scourge; rather, they see it as a random event within an indifferent universe. Here, Camus’s Absurdist philosophy diverges from traditional theological explanations: the plague, like all manifestations of evil, lacks inherent purpose or higher meaning. Consequently, the human response to it becomes a matter of personal and collective ethics. Instead of surrendering to solitude or fatalism, these characters find meaning in defying the plague through collective action, even when their efforts seem futile in the grand scheme of things.

The traditional Christian (and arguably Jewish and Muslim) perspective holds that God, in His omnipotence, grants humanity free will, thereby making individuals responsible for their actions. This theological framework challenges Camus’s assertion that belief in a perfect, all-powerful God is incompatible with the existence of evil. While there is a predestinarian strand in Christian thought, as exemplified by Augustine, Martin Luther, and John Calvin, predestination complicates the notion of divine accountability. In his M.A. thesis, Camus recognizes that Augustine’s theology struggles to reconcile human free will with innate human depravity and predestination. This failure of predestinarian views to accommodate free will does not negate the validity of non-predestinarian Christian theology, which maintains that human choices are meaningful and accountable.

The crux of the matter is that divine omnipotence does not necessarily imply that God controls human will and choices; rather, it suggests that He has the ability to do so. Camus offers no compelling reasons to dispute this fundamental point and thus may be perceived as confused when he asserts that divine omnipotence and human free will are inherently incompatible. Interestingly, even Albert Einstein expressed a similar misunderstanding of this issue.

However, there is more to consider in the spirit of Camus regarding the free-will defense. Returning to the indignation expressed by Rieux, who serves as a voice for Camus, concerning the suffering of innocent children—suffering that seems to constitute an outrage if God exists—raises important questions. If Father Paneloux had opted for a theodicy explaining natural evils, such as plagues, as the result of malevolent free choices made by Satan and his cohorts, one could imagine Rieux’s impassioned rebuttal: how could the free will of depraved beings possibly justify God’s allowing them to inflict suffering on innocent children? This type of argument has been raised against the free-will defense when used to justify the suffering caused by human atrocities, such as those perpetrated by the Nazis.

As the plague subsides, one character observes how quickly the city reverts to its familiar routines, almost as if the catastrophe had never occurred. This rapid return to normalcy may reveal a profound inability to integrate such significant suffering into the fabric of ordinary life. The message of The Plague is stark: evil is an unavoidable force that confronts humanity, compelling individuals to confront the question of their response.